The Years Rudyard Kipling Spent Searching for his son John's Grave in France

John Kipling's 1915 Remains Weren't Settled Until 2015

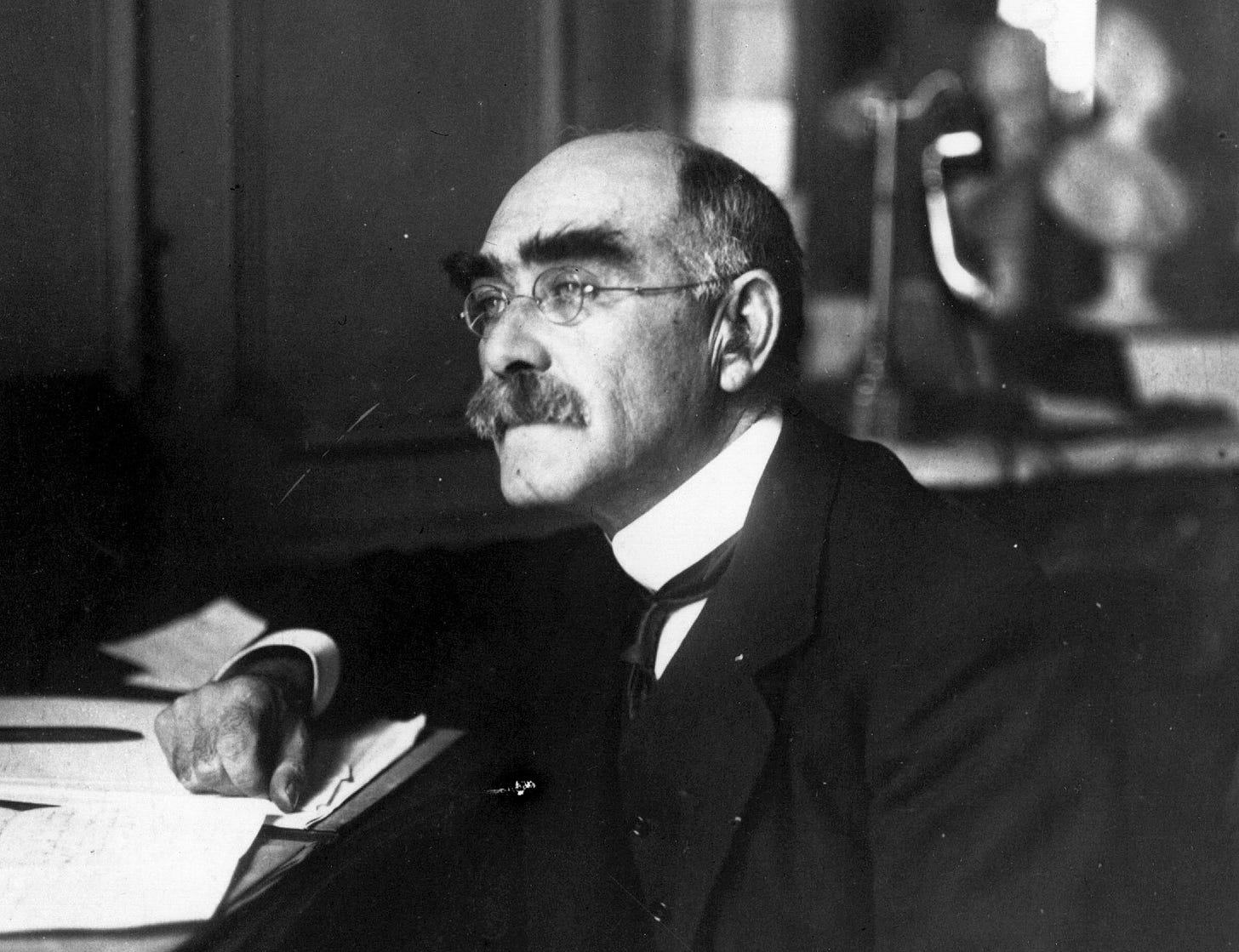

Rudyard Kipling was the poster boy author for the peak of the British Empire.

Kipling lived from 1865-1936. His best and most productive years were from 1890-1920.

Kipling’s most famous stories were classics like the Jungle Book, short stories like The Man who Would be King, and poems like Gunga Din. Here’s the Gunga Din poem in case you haven’t read it before.

After his 1936 death, Kipling was afforded the rare honor of being interred in Poet’s Corner in Westminster Abbey.

Kipling was a proponent of Empire. He was the translator of what it meant to be British in a now-bygone era.

His famous admonition to that end, and one of his most controversial poems, is the “White Man’s Burden” from 1899. In it, one stanza says:

Take up the White Man's burden—

No tawdry rule of kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper—

The tale of common things.

The ports ye shall not enter,

The roads ye shall not tread,

Go make them with your living,

And mark them with your dead!

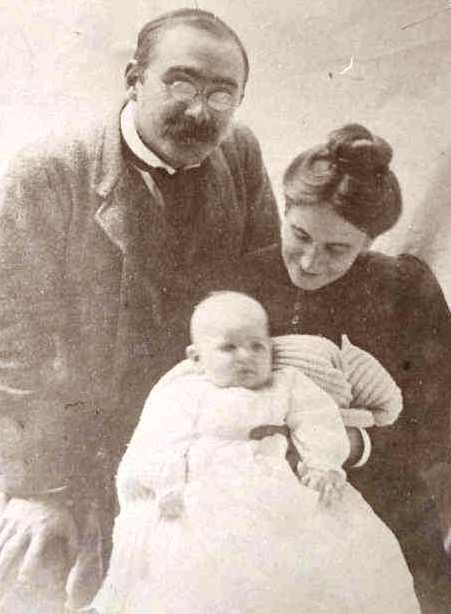

The year it was published, 1899, marked 2 years from the birth of Kipling’s only son, John.

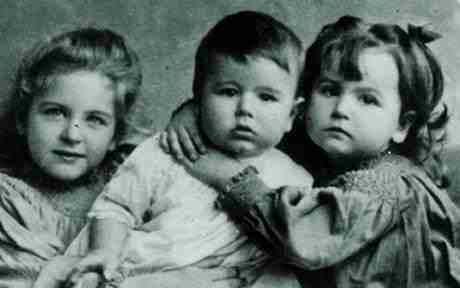

Kipling had two daughters: Josephine and Elsie. His sole son was John.

Josephine died of pneumonia in 1899 at the age of 7. She and her father caught it in New York during a family visit after a sea voyage where they initially caught whooping cough.

Elsie, in her later memoirs, said of her father: "There is no doubt that little Josephine had been his greatest joy during her short life. His life was never the same after her death; a light had gone out that could never be rekindled."

The entire line of Kiplings would, within one generation, come to an end. Pneumonia took Josephine, and the continental conflagration of the Great War took John a few years later. In a way, in an observation that I’m sure millions have made prior, Kipling’s confidence at the turn of the century matches a certain ruin by the start of the second Great War.

Kipling’s family ruin matches the British Imperial ruin at the hands of Churchill and others.

In 1862, wife Caroline was born.

In 1865, husband Rudyard was born.

In 1892, Rudyard was married to wife Caroline at ages 27 and 30.

In 1892, daughter Josephine was born.

In 1896, daughter Elsie was born.

In 1897, son John was born.

In 1899, daughter Josephine died, age 7.

In 1915, son John died, age 18.

In 1936, father Rudyard died, age 70.

In 1939, widow Caroline died, age 76.

In 1976, daughter Elsie died, age 80.

Kipling children Josephine, Elsie, and John all died childless. There were no heirs to continue the Kipling mantle. The little petit personal empire of a family was brought down by the triple calamity of disease, war, and childlessness.

Kipling’s sister Alice died in 1948, age 80, also childless.

The left has taken all this, in addition to access to Kipling’s personal papers, to simply say he was gay. Martin Seymour-Smith made this claim in his 1989 work “Rudyard Kipling.”

It’s amazing how the easiest things to take for granted are often the most meaningful and consequential ones: health, family, love. The fires that power a successful family are those that, within a microcosm, fuel a thriving empire.

Every nation relies on the strength of the families that comprise its foundation.

Since Kipling’s death, there has arisen a cottage industry of doomsayers who prophecize about why society will fall, why the regime will fall into ruin, and why there’s no escaping those historical trends.

Yet those trends are entirely reversible simply by changing the trends in the world one finds in their own household.

The discipline of personal strength leading to the blossoming of a family that then pays wider social and cultural dividends is the process by which nations are made and constantly remade every generation.

The regenerative nature of the nation is found in the continuous growth of a family, a lineage, of a people.

Kipling’s three progeny were taken by three different calamities. The passage of John was the one perhaps most poignant.

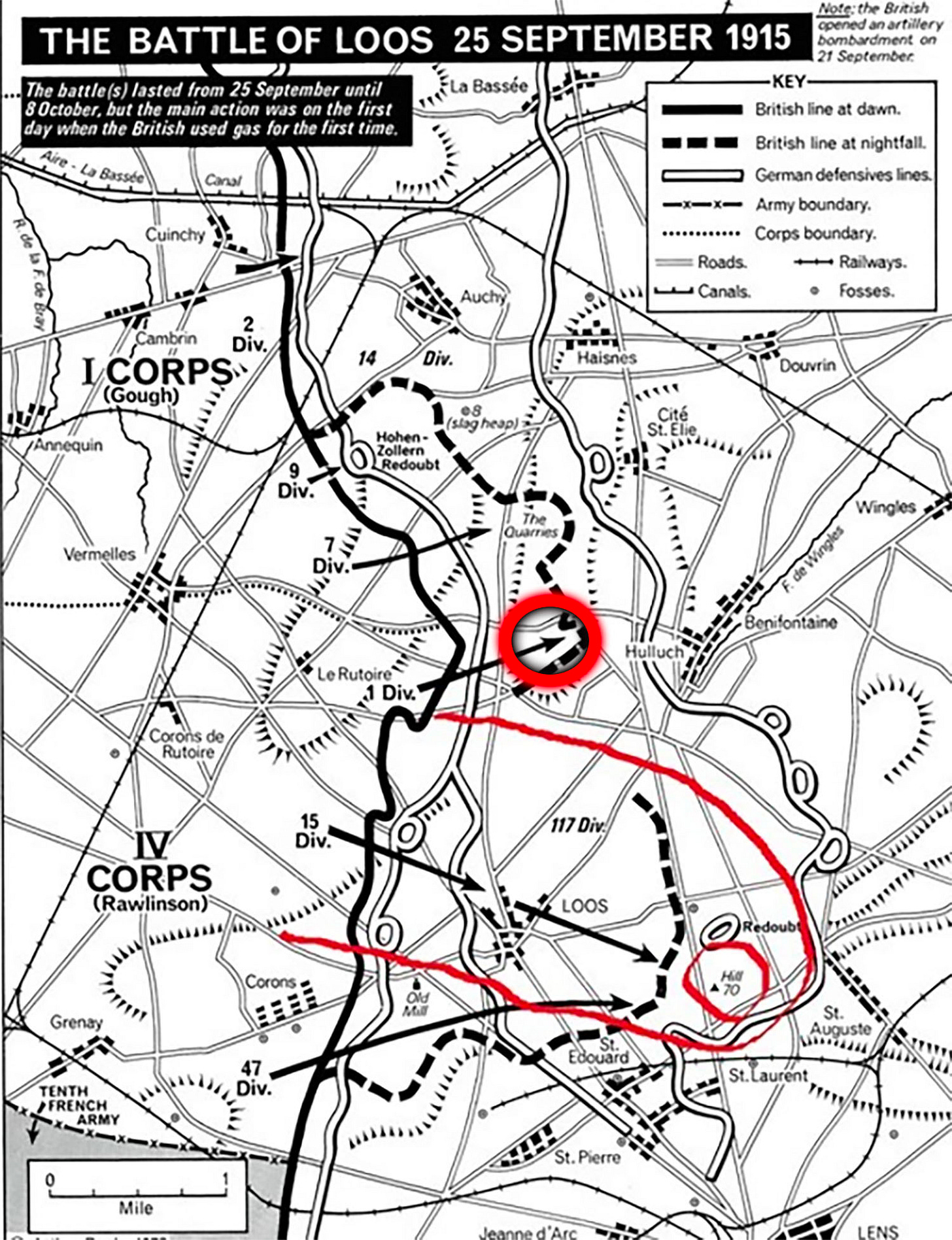

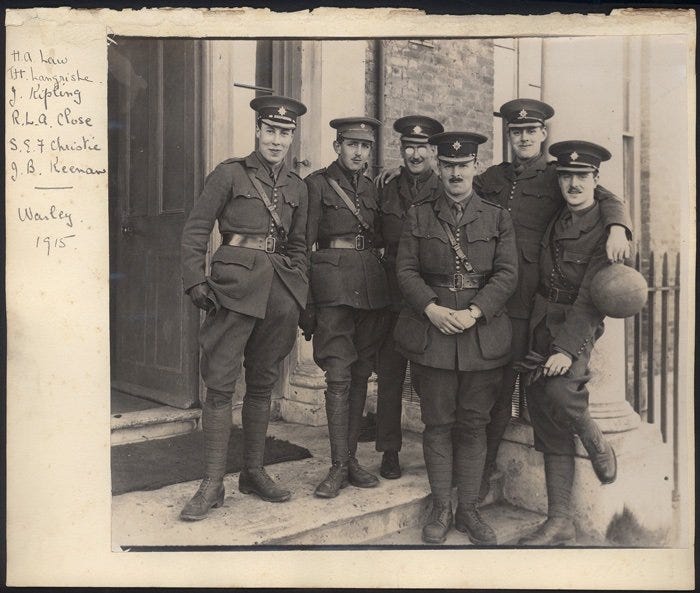

John Kipling was 18 years old, the son of author Rudyard Kipling, when he died on September 27, 1915 during the Battle of Loos in France.

Friends and family said he had a small stature, sunny disposition, and was a bit of a car buff. He wasn’t academically excellent, but more middle-of -the-pack. Average. But with notably bad eyesight.

The Battle of Loos is a forgotten battle in a forgotten war fought for forgotten reasons. It consumed 60,000 British boys, and 26,000 German ones.

John Kipling was part of the Guards Division, shown on the map as the “1 Div.” attacking eastwards in the center of the map.

Kipling was in the 2nd Battalion of the Irish Guards. In WW1, a Battalion typically had, at full strength, 35 officers and 1,000 soldiers. There is some irony that a Unionist protestant like Kipling would end up having his son serve in a battalion of primarily Irish Catholics.

His Battalion was part of the 2nd Guards Brigade of the Guards Division. A British Brigade had 4,000 men, and a Division had roughly 18,000 men.

Kipling enlisted on August 15, 1914, age 16. He died 408 days later.

He shipped off to war a year later, on August 16, 1915 from Southampton, England aboard the S.S. Viper headed for Le Havre, France, about a 120 mile journey.

His father was motivated to encourage his only son to enlist because of the twin atrocities of the Rape of Belgium and the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania.

Shortly after the war’s end, both atrocities were recognized as false war propaganda. Only in recent years, due to the dishonest academics of our modern age, are they trying to retcon those fake incidents into somehow being authentic so as to avoid criticisms of similar false war propaganda that we currently experience.

The agenda is relatively easy to notice: if you can conceal and gaslight about yesteryear’s war propaganda, it will be harder to spot the patterns of modern war propaganda. If you can suppress the obvious lies about the Lusitania, you’ll be more likely to fall for bullshit like the “Ghost of Kiev” or “Snake Island” and similar fantasies.

In Kipling’s epigraphs work, he briefly references such war propaganda and connects it to the loss of his son:

“If any question why we died, / Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

Kipling had basically bullied his teenaged son into enlisting.

John was precluded from enlisting due to poor eyesight. He failed one eye exam completely while trying to enlist. Rudyard had pulled some strings in order to allow his impairment to be overlooked. Rudyard had had bad eyes, and so the defect was genetic, it was baked into his DNA, it was inevitable.

John had trouble reading the second line of an eye chart. He had no business running around a war.

Rudyard was excited that his son was in the military though, even though he preferred the Navy over the Army. He bought his son a “Singer” car to celebrate.

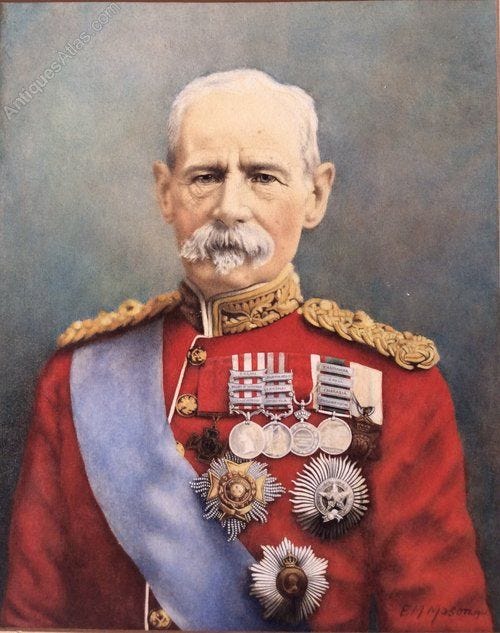

The man who helped Rudyard get John past the disqualifying medical problems was Earl Roberts aka “Bobs.”

Bobs died on November 14, 1914. A day shy of three months after when John enlisted, and 9 months and 13 days before the day John would die on the battlefield.

Bobs’ own family mirrored much of Kiplings’ in terms of outcomes. Bobs had six children, two of which were boys. Three of the children, two girls and one boy, died as babies and infants. Of the other three, two girls and one boy, the boy died at the Battle of Colenso in 1899, part of the pointless Boer War. He was one of 143 deaths during the battle. Of the two daughters, the elder daughter died childless in 1944. The younger of the two daughters, Ada, had one child, Lieutenant Frederick Roberts Alexander Lewin.

Lt. Lewin died on May 15, 1940 with the Irish Guards of the 1st Division as they invaded Norway to try and win it back from the Germans who invaded the month prior. From reports it looks like they were invading the far northern part of Norway and the Germans bombed and sank their boats. Lt. Lewin has a small memorial in Surrey.

Bobs’ lineage died in Norway at that moment, in the North Sea, on a futile mission fighting the Germans for land that would never be taken from them and, in the end, didn’t matter. The Germans surrendered Norway without a fight on May 8, 1945.

Such is the similar end of the British Empire in a nutshell: sacrificed for Polish independence in a war with Germany that saw Poland later surrendered to the Soviets.

Kipling’s lineage passed away sooner. But they would both face the same fate: both the imperial war hero and the imperial war poet would pay the price in personal trauma.

If John Kipling had just waited a few more months to enlist, maybe the patronage and waivers wouldn’t have been as easy or as possible since Bobs would have been dead. What if… what if… what if…

Rudyard would outlive his son John by 7,418 days.

But he would never know it for sure.

Rudyard and his wife Caroline would never know what happened to son John. They would wonder for the rest of their lives if he was possibly taken prisoner or injured and invalid or if he simply gave up on his duties and ran away.

‘Dog Tags’ were in their infancy, but bodies in the Great War were often buried near where they fell. The bodies were often stuck in piles or trenches where they would become consumed by the elements or by animal scavengers. The dead were buried hastily, and their graves were often poorly marked and the records poorly maintained.

The British lost a million men in the war, and an estimated 500,000+ are MIA. Good statistics on the matter are hard to come by. I suppose it’s better to avoid such analysis when the answers would be so shameful.

The British, unlike their American counterparts, don’t believe in disturbing war graves to determine identity. So its likely that these graves will never have their mysteries answered.

Which policy stands especially in contrast to the public statements etched upon the granite around most British memorials, which reads:

Their name liveth for evermore

The original quotation was "Their bodies are buried in peace; but their name liveth for evermore." But upon compromise, it was shortened to just the second half of the phrase.

The suggestion for the phrase came from… Rudyard Kipling.

John Kipling’s final resting place was thought answered around 1992, when in researching details about the internment at the graveyard St Mary's A.D.S. Cemetery, in Haisnes, France. “ADS” stands for “Advanced Dressing Station” which is essentially a field hospital on the battlefield.

Doubts remained, and competing theories considered, until it felt reasonably settled by 2015 that this was the final location of John Kipling.

The final identification took five years short of a century to establish. This page gives a good rundown of the various issues in resolving the questions around the burial and body.

Kipling is given credit for giving unknown identity graves the inscription “Known Unto God” - a description that was on his own son’s grave until July 1992, many years after John died in 1915 and Rudyard later in 1936.

The cemetery holding son John has 2,000 graves, two-thirds of whom are unknown soldiers even today. More precisely, of 1,815 burials, 218 are identified.

In a letter dated 8 days prior to his death, John asked his father to send him a replacement identification disc in case he fell during battle so that his body could be easily identified.

The replacement disk was never received. He signed the letter as a 2nd Lieutenant.

He had been promoted to a full Lieutenant, but it was the custom at the time not to change a field rank until it had been announced and published in the London Gazette. This salient little point is one in which the identification of his body later rests upon.

In 1915, all that his father knew was that his son was missing and injured in a warzone. He was not that far away in the grand scheme of things. As the crow flies, as they say, he was about 110 miles away from the Kipling home known as “Bateman’s” now held in the British National Trust.

I’ve noted on the map where the burial spot for Kipling is, in relation to the plan for the Battle of Loos. It’s the red glowing circle with a black inner glow, not the spot labelled “Hill 70.”

So, Kipling’s son’s body was where the front lines for his division were at on the first day of fighting. The battle would end up being a major defeat for the British.

I don’t want to be flip or glib here, but that’s kind of the most obvious place for his body to be with the benefit of hindsight.

On April 15, 1915, Kipling wrote to his son and his anxieties about his son’s future, “I awfully miss the little middle-week glimpses that we used to have of you and I fear that, deprived of my valuable moral and elevating conversation you may go headlong to ruin — night gambling halls, harlotry etc etc.’”

John’s headlong into ruin would come a little more than five months later.

Rudyard had a rough upbringing, having been sent to boarding school suddenly by his parents. He was a bit distant from his father, and his feelings of abandonment by his father led him to dote on his son John, and to constantly want him around. The trauma of his youth made him what we might call a ‘clingy’ parent today.

The First World War ended 1,141 days after John’s death, on November 11, 1918. It wasn’t until 1919 that Rudyard accepted that his son was not an MIA or stuck in an insane asylum with head injuries, but that he was dead. Dead and never to return.

Dead and gone. Gone forever. Forevermore.

John’s effects would be sent to his parents on January 28th of the next year. They paid out his remaining wages, 64 pounds. Which is about $5,850 in U.S. dollars, inflation-adjusted.

One has to wonder, as the years ground his body down, if the weight of wondering what happened to John crushed his spirit and soul. His output as a writer considerably slows, and what could have and perhaps should have been the best years of his literary output is barren.

You can find John Kipling’s grave among others in the Irish Guards in northern France. Hulluch on the map below has 3,400 people in it. Vermelles has 4,700. These are little French communes that, today, have no hotel lodging and 2-3 low-rent food options. It’s sleepy French farming countryside.

Here is John Kipling’s headstone there as of July 2023:

There are so many Allied graves, there are actually graveyards within sight of graveyards, just a few hundred yards away.

Take a look at this photo and notice the multiple other graveyards within sight while standing inside the St Mary's A.D.S. Cemetery:

You can probably notice the one, the Ninth Avenue Cemetery with 45 burials, in the foreground:

But don’t miss the one, Bois-Carre with 174 burials, a quarter of whom are unknown, in the background:

All of the graveyards are now surrounded by active farmland.

Kipling would sit as a Commissioner on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

He would write the official history of his son’s division, The Irish Guards in the Great War. The work took him five years to complete, publishing in 1923.

In the work, he relates an anecdote about the Battalion being inspected by Lord Kitchener four days before the Battle of Loos. The setting, scene, and expressions seem… frankly obscene with the benefit of hindsight:

Lord Cavan in the quote received a bevy of awards and ribbons and positions, dying of old age at 80 years in 1946. Lord Cavan had two daughters and no son.

When Kipling wrote the history of his son’s Division, he inadvertently wrote the history of the death of his own son. He didn’t know this at the time, he may have had suspicions about the details of where and when his son died, but all he knew is that his son was wounded but walking. That was the last he heard.

Reports said that he was seen crying from a neck wound.

Rudyard spent years walking around asking anyone if they had seen the young boy with unique eyeglasses, reportedly a pince-nez set.

The body sat around at the location near where it fell, in a place called the “Chalk Pit.” The formation still exists, you can see it close to the current final resting spot on the map below in the bottom right.

On September 27, 1915, 2nd Company approached the forests around the chalk pit mine. Kipling was in a group with two other officers, 2nd Lt. T. Pakenham-Law, full name Thomas Packenham-Law, and 2nd Lt. W.F.J. Clifford, full name Walter Francis Joseph Clifford. At 4pm they went over the breach after hours-long bombardment of the German positions. Machine gun nests opened up and wounded Lt. Pakenham-Law in the head, dying in the hospital later, and Lt. Clifford quickly.

Clifford and Kipling were shot in the same bursts, but Clifford’s body would be found and Kipling’s would not.

One eyewitness, and many claimed they saw Kipling’s demise but their stories are contradictory or otherwise implausible, was Rider Haggard. Haggard claims he saw Kipling holding a field dressing to his mouth having been “shattered by a piece of shell” and crying when, not long after, he was buried by a shell and there were few body parts to be collected.

John Kipling’s remains were in an unmarked grave from 1915 to 1919 when it was interred. Its later identification was complicated by the fact that no other Lieutenant or officer died during that small stretch of French countryside at that time. Even though he was promoted to Lieutenant, John Kipling still referred to himself the week prior to his death as a 2nd Lieutenant. So the grave of a body of a Lieutenant was incongruent.

The body has a uniform with two “pips” and not the right one “pip.”

The debate seems to have settled, but it caused 20 years of back and forth as to whether this body buried at St. Mary’s A.D.S. really was John Kipling. The British do not dig up their dead to test their DNA in the same way Yankees prefer to resolve such questions.

Here is the section of the book written by Rudyard covering the action that took the life of his son John Kipling:

Rudyard would also write a poem about a 16 year old boy named Jack who was an inspiration for British war propaganda, Jack Cornwell. During the Naval battle of Jutland in 1916, Cornwell had stood his post on the HMS Chester as other men were taken out by German fire. Cornwell died with bits of steel shrapnel in his chest, standing at his post, awaiting orders.

Cornwell was lionized as a war hero and became a major political symbol of the time.

Men should be war heroes, not boys.

In her diary, Carrie Kipling noted that the last spoken words from John Kipling to his mother were “send my love to Daddo.” He left the next day to ship off to war, his 18th birthday.

I retraced his path to the end for Kipling, in ten steps from his home transported over to France, where he died on September 27th. For having fought in a Great Global War, Kipling was still so close to home.

Kipling used Cornwell’s story from a Naval engagement to write a poem about the feeling of the young boy’s loss. Even though ‘Jack’ is sometimes a form of ‘John’, there’s no evidence according to researchers that John Kipling was ever referred to as “Jack.” This is used as a way to dismiss the poem’s impact by detaching it from the Rudyard-John connection.

It’s impossible to think that the experience losing his son John didn’t inform and shape the contours of the emotions expressed in the following poem by Rudyard Kipling. It’s just a silly academic exercise to note that John was never called Jack, since reading the poem makes very clear that the loss expressed was personal.

My Boy Jack (1916)

"Have you news of my boy Jack? "

Not this tide.

"When d'you think that he'll come back?"

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

"Has any one else had word of him?"

Not this tide.

For what is sunk will hardly swim,

Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.

"Oh, dear, what comfort can I find?"

None this tide,

Nor any tide,

Except he did not shame his kind---

Not even with that wind blowing, and that tide.

Then hold your head up all the more,

This tide,

And every tide;

Because he was the son you bore,

And gave to that wind blowing and that tide!

As the father of young boys, the poem affects me in a way that I don’t think it would if I did not have children. I frankly can’t imagine the anguish of not knowing what happened to your son for a day, week, year, decade, the remainder of your life.

The daily pain and anguish feels like the washing of every tide. The scraping of the water against the sand and the foam of the churn seems like an apt comparison to the chest-tensioning of such loss and endless feeling of such loss. The enormity of the ocean matches the enormity of the grief washing in day after day.

Kipling’s final resting place for his ashes is in “Poet’s Corner” in Westminster Abbey.

It’s just tough to rationalize all of this in the context that almost all Americans today couldn’t explain what the first World War was even about. They couldn’t tell you who were the ‘baddies’ and what caused America’s entry into the war. To say they all died in vain for nothing is almost too charitably, since they have basically all died in forgotten vain for nothing of consequence.

There was certainly nothing at stake of consequence to whittle away the valued lives of these men in their prime. To grind down an Empire to serve the needs of elites.

The real action plan underway was to plunge the Western World into a series of pointless, brutal, and meat-grinder wars. This had the consequence of serving the goal of destroying the monarchy as an institution in Europe. It also set the stage for the advent of, and fast metastasization of, Communism.

The 20 million dead, half of whom were civilians and the other half soldiers, paved the way for international Communism’s aggressive growth via infiltration, subversion, revolution, coup, invasion throughout the 1920’s and 1930’s.

The “war to end war” was not successful at that aim, but wasn’t altogether off either. The first World War was certainly the last ‘set piece’ war. It would be the last war with trenches. It would also be the last war to contain its carnage to uniformed soldiers. It would be the last polite conflict between parties, peoples, nations that cared about conventions and treaties and common humanity.

It’s hard to imagine any other later conflict with a “Christmas Truce.”

Having spent so much time on this topic, and invested so much, it has not escaped review that perhaps Lieutenant Kipling’s notoriety is fleeting. Kipling might be a known author these days, but his influence is certainly waning. John Kipling was, in most respects, average and unremarkable.

There does seem some fundamental injustice in obsessing over him and his remains while the others are ignored. The picture below shows the shine of Kipling’s grave, and the grime on his eternal neighbors.

There aren’t easy resolutions to that. I could offer some empty ones but I won’t. The one relevant observation is probably that the same fame that he has in death, was manifestly greater during his life and the pressure to perform, excel, and enlist, was enormous. He wanted to live up to the expectations of both his father, and to his father’s fans. That choice led him to France, and ultimately to his early death.

A reader commented to me verbally: "it seems as though you're, at least at one point in this, criticizing the fact that Kipling has a marked headstone."

Response: That's not the intent. Though I do have mixed feelings, and try to summarize those at the end, that there's a certain manifest injustice that so much time and effort was spent finding this one, otherwise unremarkable, Lieutenant in a war where there's 500k other unidentified graves. Walking around St. Mary's ADS, at first you're struck by how there's clearly very little foot traffic to the site and you wonder, where are the families. But then the obvious fact hits: even if the families wanted to visit, they can't visit an unidentified grave. The denial of DNA testing to produce identifications, while having some understandable cause so as to avoid disturbing their final rest, seems to be unbalanced against the interest in identifying the remains. Kipling's grave is surrounded by 1,600 other boys who are nameless burieds. That just feels wrong.