Estimating the Intergenerational Losses from Prior Major Wars

The impact on America's demographics from the dead bodies of America's Civil War, WW1, WW2, Korea, Vietnam, soldiers

When one reads about war deaths, they feel like you’re looking at an overgrown cemetery.

Those were men who died long ago, in places often far away. They are the tragic misfortunes of a prior age.

We are detached in time, so we can be detached emotionally.

It’s easy, it’s convenient. It keeps history somewhat sanitary.

It’s also not exactly true. America still suffers the burdens of those past losses.

The missing dead from these wars are the missing great-grandfathers of your coworkers, your neighbors, your relatives who were never born.

Mankind is not a series of little automatons. We are not born out of a test tube. You come from a mother and a father.

Every child that is born did so through the love of a mother who carried that baby to term. That mother typically relied on a man to provide for her, and ensure that the baby was born happy and healthy.

This is the natural order of things. Men and Women come together and have babies. That is the right and natural order.

Wars are both natural in that they express man’s violent nature, but they are unnatural in the sense that they enact such sudden violence that is so permanent.

There’s an odd paradox there. All societies are, on some level, organized in order to effectuate mass violence. But all individuals are, on some level, majorly predisposed against committing violence.

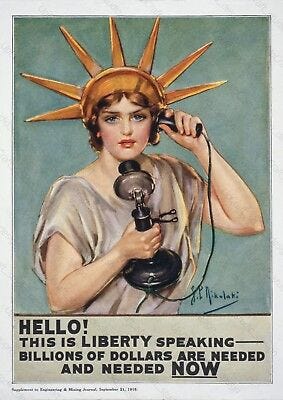

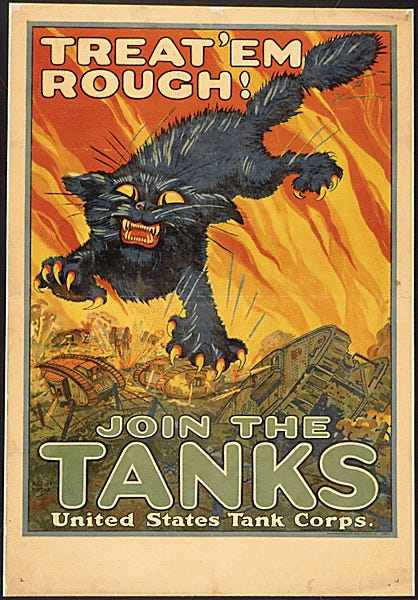

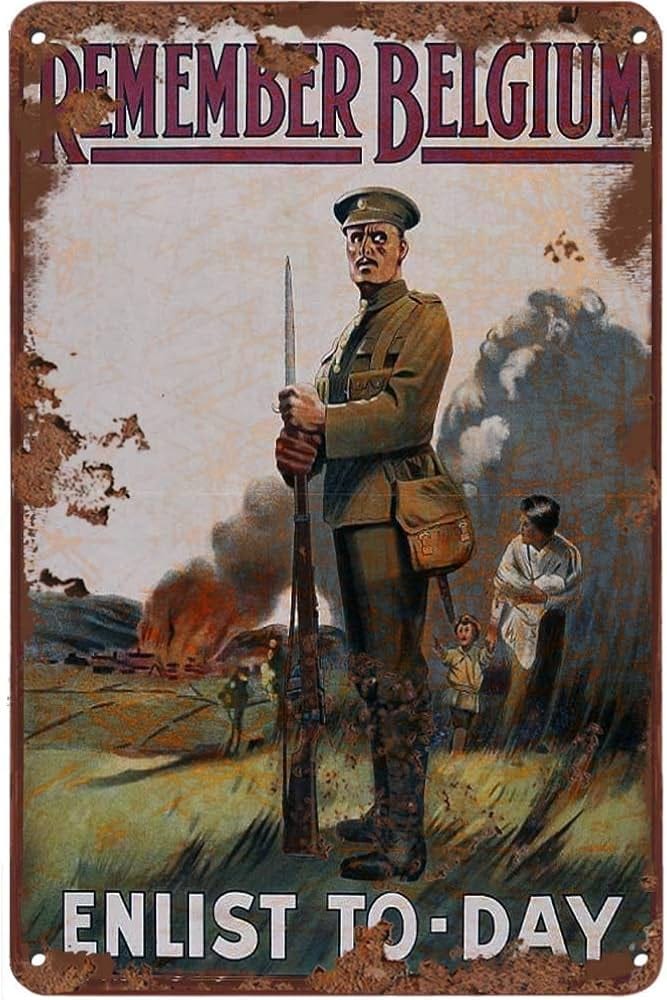

The military has studied this extensively and has found that many soldiers never fire their weapons in anger. The military uses a wide variety of psychological tricks and methods in order to dehumanize both the enemy, but even fellow soldiers, so that the loss of one’s friends and comrades do not stop the army from marching forward.

According to research by S.L.A Marshall mainly using World War II soldiers, only around 15-20% of soldiers in direct combat actually fire their weapons, meaning a significant portion of soldiers may not fire their weapons even when engaged in battle. This phenomenon is often referred to as the "ratio of fire" theory.

Many deer species—especially during the rut (mating season)—engage in highly ritualized displays and contests of dominance. Instead of immediately locking into full-force, physical combat, they often perform threat displays (such as standoff postures, antler displays, and even mock charges) that are intended to establish hierarchy without actual, injurious contact. In many cases, these displays prevent a full-scale, potentially fatal clash.

Insects, Primates, Lizards, all have many species that use ritual combat instead of risking actual injury and death.

Life, after all, is precious.

So before I explain my methodology for calculating all of this, let’s start with some common numbers and casualty counts:

Civil War: 620,000 died from 1861-1865

Average age: 25World War 1: 116,500 died from 1917-1919

Average age: 26World War 2: 405,400 died from 1941-1945

Average age: 26Korean War: 36,574 died from 1949-1953

Average age: 24Vietnam War: 58,220 died from 1964-1975

Average age: 23

Now, the vast majority of these people who are dying are men.

But if 620,000 men are dead in 1865, how many less children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, does America have as a result?

War is a depopulation exercise after all.

I think it’s fair to say that killing a man does not kill his children per se, though of course it could leave them desperate and homeless. It certainly kills his future potential children. And it certainly destroys any potential family he might make with a woman he loves.

So each death is likely a family that never formed.

There is some sort of eugenic aspect to this mass culling, I suppose it’s worth noting briefly. Fewer men means fewer suitors for a greater number of women. That probably leads to the least-desirable women to become spinsters. It takes them out of the gene pool. However, that societal benefit is likely weighed against the desperation for women, seeking to procreate, who end up choosing mates who are less desirable, more transient, more predatory. As modern women might say, “He’s not Mr. Right, he’s Mr. Right-now.” I’m not sure how you could balance the impact of those two likely phenomena, so I’m going to lazily assume that they cancel each other out.

I’m struggling with the math and statistics modeling knowledge necessary to properly compile these calculations. I need to develop a more robust model.

As a short-term cheat, I asked ChatGPT to see if it could slap together some sort of a model. Here is what it generated:

Most modern demographic analyses suggest that the overall cost of the Civil War in terms of “missing” individuals in today’s population is likely on the order of 20–30 million fewer people than there would have been had those 620,000 soldiers survived. A mid‐range estimate might be around 25 million missing individuals today as a result of Civil War fatalities.

That’s of course, about a little less than a tenth of the total U.S. population today.

For World War 1, it estimates 4.5 million individuals, descendents, are missing.

For World War 2, it estimates 6.2 million individuals, descendents, are missing.

For the Korean War, it estimates 450,000 individuals, descendents, are missing.

And for Vietnam, it estimates 262,000 individuals, descendents, are missing.

These five conflicts account for, according to ChatGPT’s back of the napkin math here, roughly 36,412,000 missing people. Now this missing bloc is spread out over decades, so some of those 36 million were missing from 1900, and others from the 1930s, and so on.

Considering that most of these war dead, and their descendents, are whites due to the military’s combat missions being segregated during these wars, it’s also worth considering the impact of those casualties on the demographics of America.

War has depopulated America, and that void has been naturally filled via open borders with immigrants.

I hope to come back to this concept sometime and develop more details on a more robust statistical model to support this thesis.

comment emailed from a reader:

This is an amazingly good essay. I'm going to forward far and wide.

It reminded me of a poem that I think was written by Chesterton entitled "Men of England."

The men who lived for England,

They have their graves at home;

And beasts and birds of England,

About the cross may roam.

But they who fought for England,

Following a falling star,

Alas, alas for England,

They have their graves afar.

And they who rule in England,

In stately conclave met,

Alas, alas for England,

They have no graves as yet.

I read this poem over 5 decades ago and probably have scrambled the words some. You can probably find it online and verify who wrote it.